Cutting Speed – Freedom of choice

As a machinist working for the ABC or XYZ company you don’t have a lot of variables that you personally select in your day-to-day duties. You don’t select which machine tools to purchase, you don’t pick which part to machine and you don’t generally choose the tools in the tool crib or the coolant in your machine.

There are three items that you can select every day for each part on the machine: the speed, the feed rate and the depth of cut. These variables all affect tool life, so all are important.

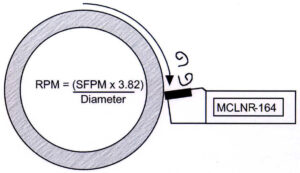

Last month we discussed using the surface footage value in our part programs instead of using a RPM value. Using the 3.82 constant in the program reminds people to think in terms of SFPM rather than RPM when selecting cutting speeds.

In training classes I always compare machining speeds with driving speeds. You wouldn’t look at the tachometer to see how fast you’re driving – the speed of the engine is not a good indicator of the car’s speed. The machine’s RPM is not a good indicator of the cutting speed either.

The spindle speed is one of the factors that machinists select, so sometimes they change the spindle speeds (in RPM), guessing until they find one that works. Many older machinists have a good feel for the best RPM in a given situation. This understanding is typically based on years of experience. However, as I point out to students, we don’t want to take 20 years to learn this stuff.

So, where can we find SFPM values to use in our programs? There are certain rules-of-thumb that should work with most applications.

Last month we discussed drilling and tapping. With general steel types (1045 plain steel) using HSS tooling, I start with 100 SFPM for both a spot drill and a twist drill. When tapping, the rule of thumb is to use 1/3 of the drilling SFPM value.

When using 316 stainless steel some people use a SFPM of 55 when using HSS drills. The 1/3 adjustment for tapping would tell you to select 18 SFPM for tapping.

With carbide tooling, a good rule-of-thumb is 500 SFPM for standard turning speeds. This is like driving at 60 MPH, not fast but safe. I use this value as a general gauge for SFPM values. For tougher material (4140 pre heat treated steel) I would slow the speed to 350 – 400 SFPM.

When milling, we use lower cutting speeds. Multiple flute cutters result in an interrupted cut and normally require slower speeds.

Selecting the correct cutting speed is a judgment call. Some machinists are always conservative. This can be detrimental to the tool cutting properly. Sometimes you just have to run the tool as fast as the manufacturer recommends to get the tool to work correctly.

On the other hand, some people are very optimistic. They tend to start with the highest SFPM values with little regard for long-term tool life. You can’t experiment with SFPM if you damage the tool on the first test.

People working in the machine tool industry often favor this optimistic method. They are on the “cutting edge” of technology, working with the newest and fastest machines. Just remind yourself that even with new machine tools and fast cycle time estimates we’re still talking about carbide against metal.

Whether we wish to be conservative or optimistic, we need to utilize a cutting speed that efficiently makes parts without changing tools all day.

We all have the same challenge, finding the SFPM that works in each unique situation. Once you find the SFPM that works, record your result. This hard-won knowledge is priceless. Once you have it you can then make the correct judgment between the conservative and the optimistic.